Effective test utilization remains a critical challenge for clinical laboratories, with misapplied diagnostic tools contributing to unnecessary treatments and higher institutional costs. Rebekah E. Dumm, PhD, the medical director of bacteriology, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and molecular syndromic infectious disease diagnostics at Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, highlighted how diagnostic stewardship programs can optimize the ordering, performance, and reporting of tests to improve patient outcomes while maintaining laboratory efficiency.

“Diagnostic stewardship is about the right test for the right patient at the right time,” Dr. Dumm said during a presentation Friday at the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) annual meeting in Boston. “Both diagnostic stewardship and antimicrobial stewardship really work in harmony to accomplish goals of improving overall patient care and outcomes” (Figure 1).

Dr. Dumm, a medical microbiologist and assistant professor of pathology and immunology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, drew on her roles in clinical and academic pathology to emphasize the intersection of laboratory stewardship—which focuses on managing resources, quality, and cost efficiency—and diagnostic stewardship, which is defined as modifying how tests are ordered, performed, and reported to guide clinical care. “These are both complementary approaches, and the line between them is often blurred,” she said.

Using gastrointestinal (GI) pathogen panels as an example, Dr. Dumm described how preanalytic and analytic considerations influence test utilization. She noted that although molecular panels offer rapid detection, their higher cost and variable clinical impact require careful oversight. “Most cases of acute gastroenteritis are caused by viruses, which may require only supportive care,” she said. “Some targets on these panels have low prevalence and therefore a low positive predictive value, which can limit their utility.” She referenced a Stanford study showing that, for rare pathogens on GI panels, only a small fraction of previously positive results correlated with clinical disease, underscoring the need for selective testing and interpretive support.1

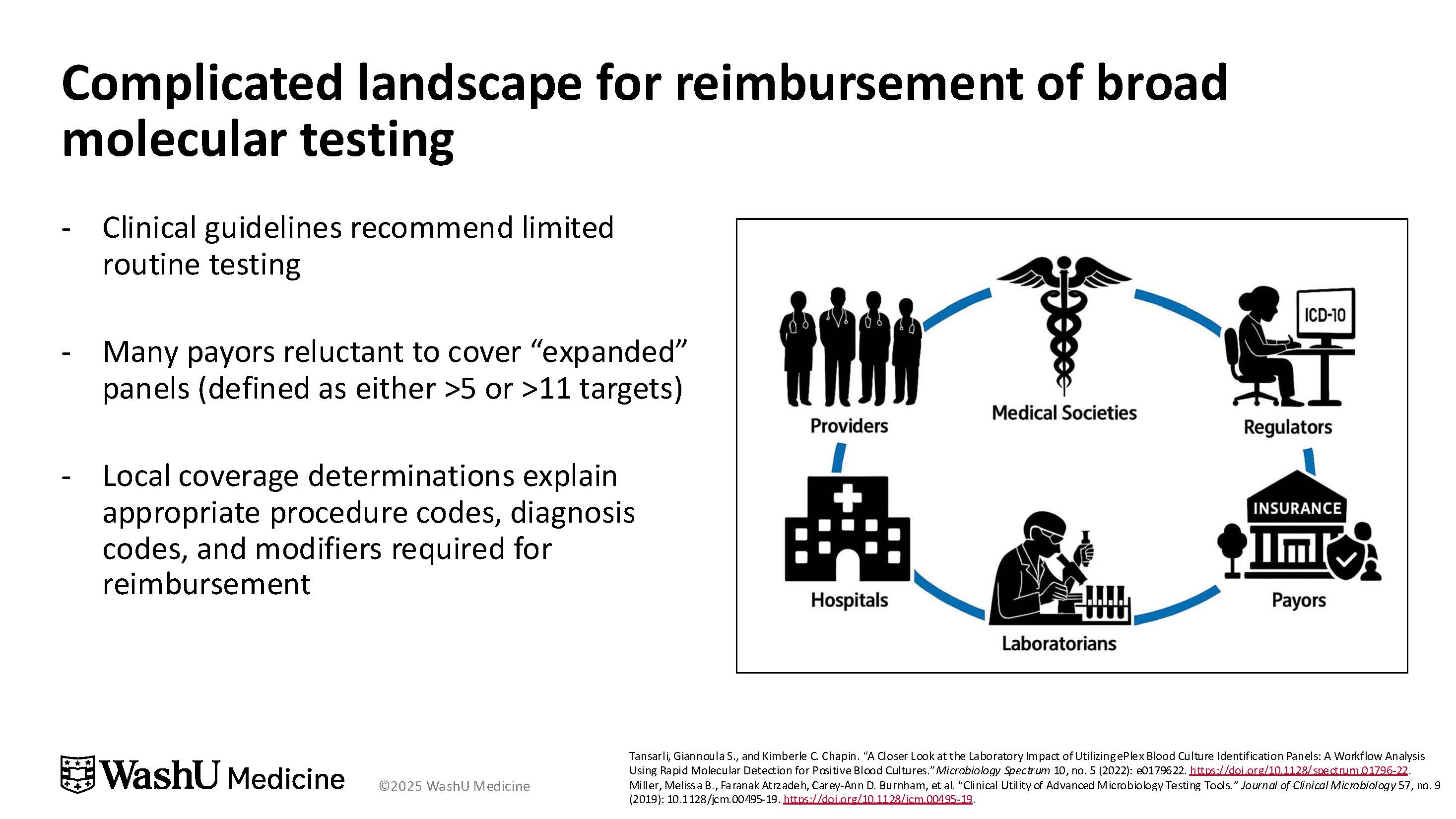

Reimbursement challenges are a significant factor, said Dr. Dumm (Figure 2). Clinical guidelines generally recommend limited testing for acute GI illness, which leads insurers to view “expanded” panels (with more than 5 or more than 11 targets) as unnecessary. As a result, reimbursement often requires strict criteria—such as ordering by an infectious disease or GI specialist for immunocompetent patients, or by oncology or critical care clinicians for immunosuppressed patients. “The reimbursement landscape for these broad panels is extremely complicated,” Dr. Dumm said. “Institutions face higher overall costs when tests exceed guideline-supported use.” She noted that the uncertain clinical impact of some rare targets further complicates justification for routine use, reinforcing the need for diagnostic stewardship.

Dr. Dumm also discussed sequencing-based diagnostics for meningitis, encephalitis, and sepsis, highlighting both their sensitivity and interpretive challenges. Data from a UCSF study of cerebrospinal fluid sequencing demonstrated that metagenomic testing identified infections not detected by standard methods, but its sensitivity relative to a composite of conventional tests was only about 63%.2 She noted that a substantial portion of findings could represent incidental or false-positive results. “When we have those positive results, they often require expert interpretation in order to make sense of them,” Dr. Dumm said. She emphasized the importance of framing testing within clinical context to maximize patient benefit while minimizing unnecessary interventions.

Behavioral interventions also play a role in guiding test utilization. Dr. Dumm highlighted the use of choice architecture, selective reporting, and eye-level reporting—methods that nudge clinicians toward preferred testing practices without restricting clinical autonomy.3,4 “Traditional efforts, like education or one-on-one engagement, are often not widespread or long-lasting,” she said. “Incorporating behavioral nudges can help clinicians work toward preferred options while maintaining autonomy.”

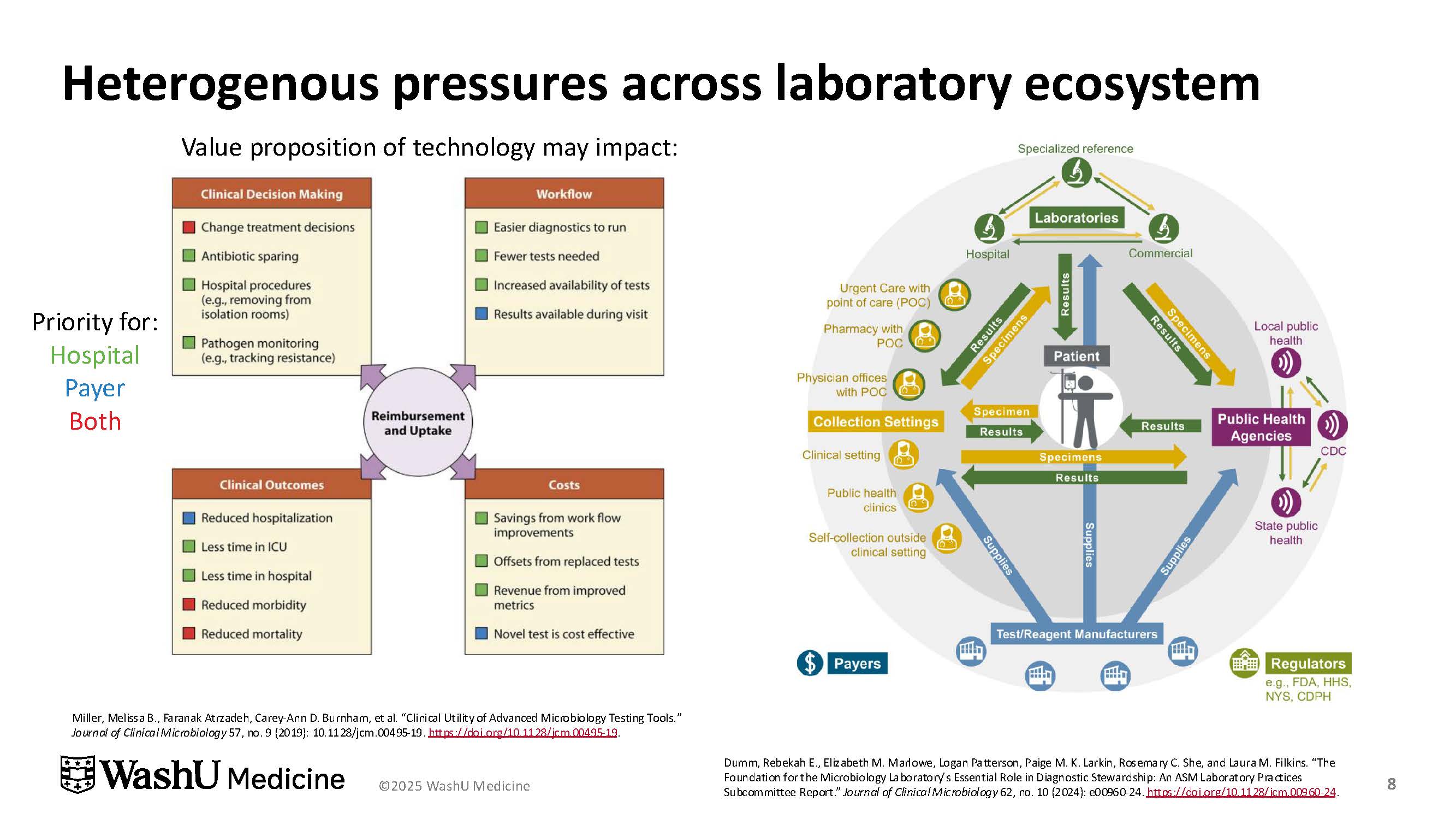

Dr. Dumm stressed that diagnostic stewardship requires collaboration across the laboratory ecosystem, involving infectious disease specialists, clinicians, nurses, information technology teams, and hospital leadership. Interdisciplinary efforts help laboratories align clinical priorities with cost considerations and institutional metrics, while also addressing the pressures of reimbursement and evolving testing technologies (Figure 3).

Ultimately, Dr. Dumm concluded, clinical laboratories are both incentivized and obligated to steward tests to provide optimal care.5 “Diagnostic stewardship is designed to improve patient outcomes, usually through decreased inappropriate testing or reduced patient harm from wrong, delayed, or misdiagnoses,” she said.

References

-

Baghdadi JD, Coffey KC, Leekha S, et al.Diagnostic stewardship for comprehensive gastrointestinal pathogen panel tests. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2020;22:11908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-020-00725-y

-

Benoit P, Brazer N, de Lorenzi-Tognon M, et al. Seven-year performance of a clinical metagenomic next-generation sequencing test for diagnosis of central nervous system infections. Nat Med. 2024;30(12):3522-3533. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03275-1

-

Jackups R. Clinical decision support tools for microbiology laboratory testing. Clin Microbiol News. 2020;42(5):35-44. doi:10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2020.02.001

-

Advani SD, Claeys K. Behavioral strategies in diagnostic stewardship. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2023;37(4):729-747. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2023.06.004

-

Claeys KC, Coffey KC, Morgan DJ. What is diagnostic stewardship? J Appl Lab Med. 2025;10(1):130-139. doi:10.1093/jalm/jfae130